Message in a Bottle

So far in these blogs I have not mentioned where programming paradigms fit. There is a reason that imperative programming versus declarative programming or functional programming vs object oriented programming have not entered the discussion. These paradigms are about ways of writing code and not about how to determine what components make up a system or how to structure them.

However, that’s not to say that there are not lessons that can be learned from examining these paradigms and applying some of the techniques used to the larger problems at a system level. During this post you will see me draw some parallels.

How to design for change?

As with most things in software there’s no single, definitive answer to this question. However, I think that there are a number of techniques that can be adopted to help identify where to ‘cleave’ a system into separate components and how to minimise the inertia introduced by the adoption of an abstraction.

I mentioned earlier that focusing on the model of the static elements of data as a data or object model in isolation can lead to focusing on the abstractions early, before the problem space is fully understood.

One technique I use to avoid this issue is rather than modelling the static view of the data, model the dynamic flow of the data through the system. Think about what events are raised and the actors that raise them? What transformations and enrichment has to happen to a piece of data in order for it to result in the required response or the required end state?

If you model a message, every point at which the message needs to be transformed into a new message becomes a potential component. It will frequently be the case that in order to transform the message additional information and some kind of external trigger is required. Thinking about whether this new information or new trigger should be the responsibility of an existing component or a new one is the way that you can decide whether the current model of the architecture is sufficient or requires change.

Examining flows of messages tends to ‘discover’ what are the major components within the system. Thinking about the timing of the event flows will lead to a discussion of whether the components you are modelling are able to communicate synchronously or asynchronously.

Each of these messages can be thought of as a piece of immutable data that is either the input to or output from a component of the system.

If you model the external events as messages that get enhanced to produce a new message then you can think about what additional information is required at each step to create the enhanced message. This process will drive out the components and the key responsibilities of each. It should also lead to the discovery of other external interfaces required by each component and suggest local optimisation’s such as a data store.

By taking this approach databases and other data stores become localised optimisation’s. As such the static structure of data and, by extension, the static models of the data in the software (schemas, object models, etc.) can be determined by modelling the transformations and enhancements of the messages carried out by that particular component of the system.

Keeping in mind this view of the component as transformer/enhancer of messages each major component in the system can be seen as analogous to a huge ‘function’ in a functional program. Something that takes in immutable data as input and returns the expected (immutable) output.

If the component needs multiple inputs from different sources these can be modelled as multiple messages to multiple functions. It is idealistic and unrealistic to imagine that the inputs to each component will arrive reliably and at exactly the moment required to carry out the job but dealing with these tricky details is, again, a localised optimisation.

It’s also worth pointing out that ‘components’ in this context are not necessarily separate deployment units with remote network calls. They can be ‘packages’, ‘modules’ or high level ‘namespaces’ within a larger deployment unit. In fact, there is a good argument to be made for keeping these components in the same deployment unit until it’s recognised that either their responsibilities, timing, semantics or non functional concerns are different enough to warrant this level of separation.

Databases are localised optimisation

It may seem strange, especially to the developer used to standard 2 or 3 tier architectures, to think about a database as a localised optimisation as typically a database forms the beating heart of a system rather than a mere implementation detail.

However, thinking in this way can be quite liberating to the software architect. Imagine an ideal system which has an unlimited amount of memory and processing power and never loses data due to downtime. In this idealised system a secondary persistent data store becomes unnecessary. Why have a data store if you readily have your data to hand in memory.

If the persistence of data is taken out of the equation for a while you are liberated from modelling data ‘at rest’ and, as I’ve already discussed, modelling data at rest can lead to strong data coupling of components and the overloading of responsibilities on a single component. The danger is that the database becomes a ‘catch all’ for every piece of data because it’s convenient. The database is always there and always on so why not use it to store this and that?

There’s nothing inherently wrong with modelling data ‘at rest’, in fact it’s a valuable technique, but frequently it becomes the single minded focus of the system designer. This leads to some of the early optimisation’s that I’ve talked about in earlier posts - the early imposition of canonical data models being primary amongst them.

So, how exactly do you design a system without considering a data store as a starting point?

It comes back to modelling the ‘flow of data’ rather than modelling the data as a detached separate concept. If we look at the messages that are required for a system to carry out its requirements we can model several things.

Message Content

The easiest and most obvious thing to model with regard to the messages in a system is the actual message content. However, this is the last thing I tend to focus on as concentrating on the detail of the data required leads to a focus on the data without context to the problem. I’ve found this often leads me to start modelling details about the entities that are not relevant.

As a naive example, if I assume I need information about a college student in my system I might start modelling the courses they are taking and that might lead me to model their lecture times and teachers. However, if the system is only required to manage the students course fees most of this information is irrelevant to the problem. Although in this simple example that is obvious, I’ve seen much more subtle assumptions creep into data modelling that have not only led to the capture, storage and maintenance of redundant data but the inclusion of this data has led to the development of redundant business processes and the code to support them. This often happens over time in small increments and, like the parable of ‘boiling a frog’, is never noticed.

Message Source

Identifying the source of a message in a system is key. Especially if the source is external.

Thinking about the source of the message helps identify some major architectural characteristics.

- Timing - when and what triggers the message?

- Sensitivity to latency of response - is it critical that the response (if there is one) is received immediately or can the source continue as long as the response is received in a ‘timely’ manner (how long is timely).

- Frequency - how often is message sent?

- Volume - how much data is it likely to encompass?

- Internal/External to the system context - is this source something you need to design/implement?

- Responsibilities - what is the ‘source’ of the data responsible for and what is it expecting the ‘target’ to be responsible for?

- Accuracy/completeness - how accurate and/or complete will the payload of the message be? Do we need to validate and enhance the message from other sources?

Message Target

This is the mirror of examining the source of the message but looking at the message flow in the opposite direction can give different insights into the same points as examining the message source. I find that examining the message target is particularly useful for clarifying the latency, timing and responsibilities. If you deliberately think about the source’s expectations around latency, timing and responsibilities in isolation and then do the same for the target’s expectations any conflicts between these two are where your architectural decisions lie. It’s also useful to apply role playing techniques and have people play both the message source and the target.

Message Flow

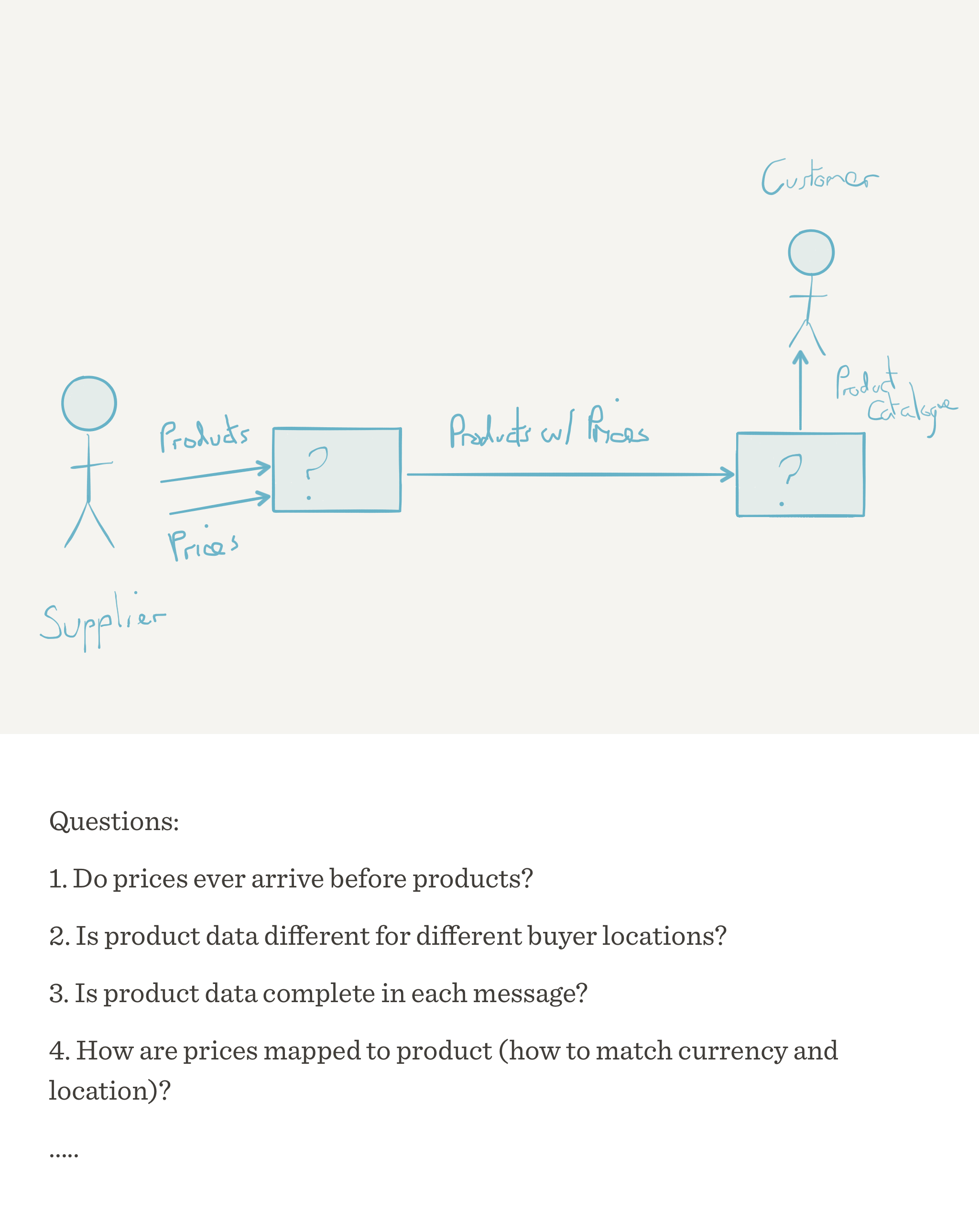

Here is a simplistic example of how modelling messages helps to drive out possible architectures. This example is by no means complete or representative of a specific architecture but simply a ‘straw man’ for discussion.

If we imagine an eCommerce system, one of the things we would need to do is capture products and prices from our suppliers.

As we can see by examining the flow of messages we are left with a number of questions around message timing, sources, targets, frequency, completeness, accuracy. Looking at even this simple example we have to ask:

- Have we got the initial responsibilities of the sources and targets of the messages correct?

- Can we determine the sequencing of messages?

- Have we got time sensitive messages?

- Does message order matter?

- What latency can we accept?

- What do we do with incomplete payloads? (Answering this in detail is dependent on message content as not all of the message payload will have equal importance)

Notice at this point I have made no judgements on how I might hold state (databases, etc) or even if I will need to hold state, let alone how I might model the message payload.

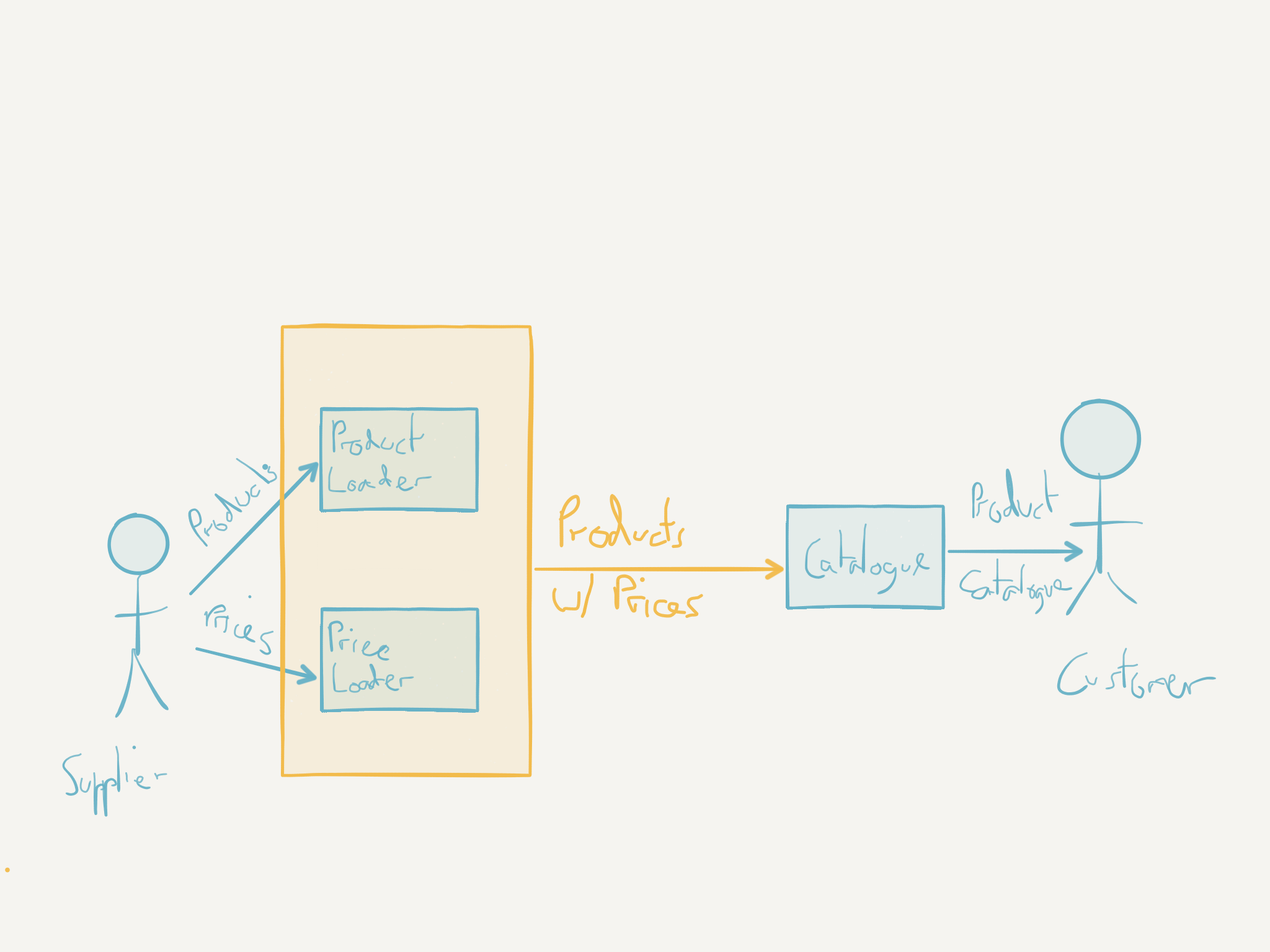

By digging into these questions we might extend this initial naive model like so:

At this point we have firmed up the roles and responsibilities of our components a little bit but these are still logical components and are not in anyway representative of the deployment units we may chose. At this point we may still consider the system as one giant monolith or, as we break it down further, we may decide to create a number of microservices1.

We still have a lot of questions about timing, latency, sensitivity to data loss, etc. but I hope this example has started to show how just thinking about the messages for even a few minutes starts to raise the right questions?

Be conservative in what you do, be liberal in what you accept from others - Postel’s law

If each component in the system accepts a message or messages from an external provider (either another component of the system or an external actor) then the question to be asked is what to do with the message received.

In the ideal situation, where the message is completely under the control of your system, it will already be in the appropriate format for your component to parse and process. However, frequently the message will either be raised by an entity external to your system and, even when it’s another system component, if the calling semantics are not in-process and/or enforced by a statically checked API then your component will still need to validate the message and enforce some kind of ‘contract’ on the context and shape of the data.

When carrying out this contract enforcement it’s a good idea to try and obey Postel’s law. Accept the message and validate the expected inputs only for the parts of the message your specific component is interested in. However, you don’t have to reject a message that sends data that your component is not interested in. In that case it is possible to simply drop data of no interest. With some thought, it is also possible to accept data in a slightly different format and transform it to the format you require. Although care should be taken with this approach, as in many cases you will be making assumptions that may not be valid and the transformation itself can be a lossy process, for example, transforming a decimal number to an integer. The decision to reject a message is always available of course, and for the sake of safety and security is frequently a good option, however you should always make this decision deliberately and with cognisance to the impact.

In all cases, whether the message is accepted or, even more so, rejected consider logging the message in it’s raw format at the point of reception by your component.

At this point it’s worth a quick sidebar on the subject of logging. In the case of logging events raised internally by your system adopting a standardised approach and format to your log messages makes it much easier to automate searching and parsing of the messages once collected. See David Humphrey’s talk on logging for some pointers on how to log within an application or service.

However, I am talking about logging the message at the boundaries of the component. In this context we want to maintain as much of the original format and semantics of the message as possible, this ideally includes the ordering of the messages. Typically logging the messages at the boundary of the system will involve writing the message to a data store in it’s raw format. The simplest way to do this is simply to serialise the message directly to disk in a file as any attempt to coerce it into a different schema for a database is inherently more likely to lose the original format and order.

I will also reveal my bias towards event sourcing, message middleware and streaming solutions. My reason for liking these approaches are that they often provide the ability to log the messages received or produced by a component at it’s boundaries as a matter of course with little additional effort.

Again, drawing parallels with functional programming paradigms, pushing the validation and transformation of a components messages to the ‘edges’ of the system is pretty much the same concept as pushing state changes to the edges of the system which is frequently a mantra of functional programming.

Keep raw message format

If you keep the messages flowing into your system in their raw (unchanged) format and order for as long as possible and pass them around the ‘components’ of the system you gain a number of advantages.

Each ‘component’ in the system can decide what information to take from the message, ignoring anything it’s not interested in.

It can also derive information from the order in which messages arrive but this causal derivation is only possible with a system that maintains the order of messages. This is where systems based on appropriate messaging infrastructures that guarantee delivery of a message in the same sequence as it was written (usually within some well understood constraints) are extremely useful.

Order matters

Why is the order of messages important? With total or partial ordering of messages maintained it’s possible to persist messages over a long period of time along with the logical timing of the messages relative to each other. This makes it possible to think of and implement a component to answer some question of the data that relies on the original sequence of events that raised the messages but some time later. In other words you don’t need to know the questions that may be asked of the data ahead of time and design your data model and processes to handle these possible questions. Instead if you keep the original format of data flowing into the system in it’s original order it’s possible to replay those messages in the same order into a component implemented after the messages creation.

Good systems are like sauces, it’s all in the folding and reduction

Another side effect of considering systems as components that consume ordered raw messages is that each component can be thought of as processing a stream of messages. The result of this consumption may be more messages emitted to other components or to users. Alternatively, it may be some change in the state of a localised store (remember this is a localised optimisation). In any case the entire component can be thought of a large function that either maps over the stream of messages transforming them or folds over (or reduces) the stream of messages to produce the desired result.

If you are not familiar with functional programming paradigms that previous paragraph warrants some explanation.

‘Mapping’ over a collection is the concept of applying a function to each element of the collection in turn emitting a new transformed element to a new collection.

Whereas a ‘fold’ is the concept of applying a function over each element in a collection to produce a single result (which could also be a collection of a different length to the original). Typically, this function takes two inputs, an accumulating ‘result’ and the current element from the collection being folded over. A folding, or reducing, function takes each element, makes decisions and/or transformations and accumulates the result. The simplest example would be to sum up a collection of numbers.

In the case of a larger component, it might be responsible for consuming, transforming each message from a stream of messages (in a queue or sent from another component via a synchronous mechanism like HTTP). It might then emit the resulting transformed message by sending it to another component for additional work. This would be synonymous with a ‘map’ function.

Alternatively, the component might consume the messages and accumulate some result (possibly statefully in a data store). This would be synonymous with a ‘fold’ or ‘reduce’ function.

This analogy breaks down slightly when we consider that we don’t have completely reliable networks, infinite memory or instantaneous processes. However, starting by thinking about each component as if it fits into this model does have some major advantages.

Role of a component?

Thinking about how to consume a message, transform, enhance and emit results focuses us on the roles and responsibilities of each component.

However, we have to do this at the right level of granularity. We don’t want to design a system that has a single low level function. This is another reason that I leave looking at the detailed content of the messages until later in the design lifecycle and always bear in mind that each ‘component’ does not have to be separate deployment unit.

Considering the messages at a larger granularity tends to allow us to imagine each component as a much higher level function, for example a message could be an order, a trade, a product, or even an entire product catalogue. We should also group these ‘functions’ together based on their responsibilities, i.e. messages that may return a single product or multiple products would sit in the same component. However, having many messages with different contexts dealt with by the same component may be warning sign that this is actually more than one component2.

Composable/Decomposable Components

Another side effect of thinking about each component as a very high level function also lends itself more to considering the messages as immutable.

What is the advantage of having immutable messages? If a message doesn’t change but a component always creates new messages this leads to a design that is easier to break down into smaller components, assemble into larger components and scale out horizontally. This means that this way of visualising the architecture leads to a design that has less inertia to change.

Explicit Side Effects

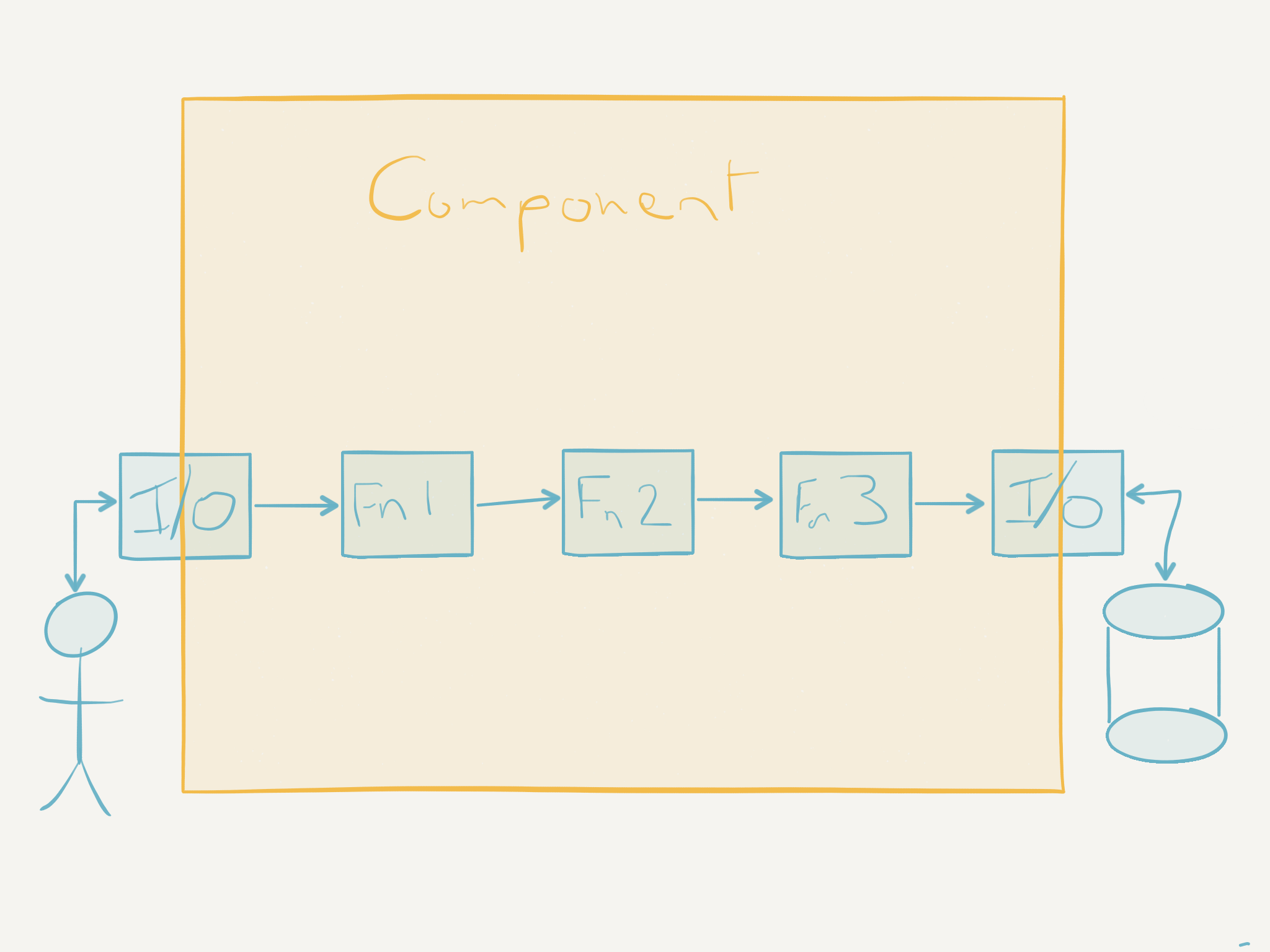

One of the major points of the functional programming paradigm is to make side effects explicit and obvious as well as pushing these to the ‘edges’ of the component.

If you are not familiar with functional programming this might not make much sense. Most FP languages and approaches tend to emphasise ‘pure’ functions. A ‘pure’ function is one that only operates on the inputs given and produces an output without affecting anything else.

This means that given the same input it will always result in the same output regardless of how often it’s called. The implication of keeping most functions pure is that most will do no input/output or state changes.

This may seem fairly useless at first thought. If a component is unable to accept input or produce output it will not be able to do anything.

Of course in reality some functions will have side effects but by keeping most pure (only dependent on their inputs) these functions will gravitate towards the ‘edges’ of the system. If we imagine the functions in a component as a chain of ‘boxes’ that take a message and output another altered message, the function at the ‘start’ of that chain has to accept input and the function at the ‘end’ of that chain produces some output.

So thinking about each component as a function with side effects at the input and output ‘edges’ again supports composing components. This means that we can deploy several ‘components’ composed together in a single deployment unit but by maintaining this component level discipline around explicit side effects at the edges of each logical component we have clear boundaries or ‘seams’ along which we can later cleave this deployment unit into smaller units or compose it with others to make a larger deployment unit. Again this supports future changes. In addition, this discipline means that logical components become easier to rewrite or replace with components that have different effects.

Immutable components

Considering each component as a high level, large granularity function can also fit well with the recent concept of delivering code as immutable deployment units, although it’s not a prerequisite. This approach has been well supported recently by technologies like Docker. If we consider the deployment unit as an immutable, versioned snapshot we can simplify issues like rolling back changes by redeploying the previous immutable version of the component.

Conclusions

What about Object Oriented Programming?

So where does this leave a paradigm like object-oriented programming? Well, if we look at Alan Kay’s definition of OOP:

OOP to me means only messaging, local retention and protection and hiding of state-process, and extreme late-binding of all things.

- Alan Kay

this definition shares a lot of the concepts that I highlighted in deriving component design. Therefore, if we consider OOP as fundamentally message passing and local state this fits really well with my functional programming analogy to components.

I think the only danger with thinking about components as OOP ‘classes’ is that most developers exposure to OOP is far from Smalltalk or Lisp (which is what Alan Kay had in mind). This focus on ‘classes’ will frequently slip into thinking of mutable state and deep inheritance hierarchies which can lead to muddling responsibilities and entangling our designs.

Consider Data in Motion

I hope that I’ve given some food for thought about how to discover components in a system by looking at data but considering the data in motion rather than at rest. I also believe that the details of the data are less important in making high level decisions than the view of the data as messages flowing through a system.

In this blog I’ve only really provided a high level sketch of how I design systems. I haven’t talked much about specific techniques (like Domain Driven Design) or diagrams (UML, etc.) to express the mental model of the system, and that’s deliberate. Those things are important and can be incorporated into my approach as required but I really just wanted to outline some ways of thinking about systems that help me. As with all things you read and try, YMMV but I hope these thoughts are at least of interest.

-

You will also notice I’ve used a notation that bears a superficial likeness to UML but it’s actually no particular notation (actually in UML this would be best represented as a communication diagram with different symbols for interfaces, controllers and entities). I am agnostic about notation, but I would suggest you establish a notation that works for whatever you’re trying to convey to your audience. Adding a key to your diagrams for anything in your notation that is not obvious or you want to highlight is also useful as it saves your audience having to context switch to a tutorial or similar to understand your meaning. ↩

-

Remember not to conflate ‘component’ and ‘deployment unit’. They are not synonymous. ↩

Leave a comment